Hamstring strain exercises from a pilates perspective

Fri,Sep 02, 2016 at 12:45PM by Carla Mullins

Hamstring strain exercises from a pilates perspective: treatment and exercise to promote optimal healing

With an increased participation in the various codes of football, Autumn (Fall) can often mean a rise in hamstring injuries; in fact a recent report from the Australian Football League (AFL) found that hamstring strains are still the number one injury in the game in terms of both incidence and prevalence (missed games) (1). Rugby Union and soccer are also showing high levels of hamstring injuries. However football is by no means alone in producing hamstring injuries: many popular activities from running to judo and dancing to skiing have reported frequent occurrence of hamstring strain. Spring is another fun time for injuries associated with running and that get ready for summer feeling.

This article is written to address the injury of hamstrings. Movement Educators have a vast strategy of skills to strengthen and helpful prevent injuries. However, injuries occur and this is our focus and we will be looking at:

// A review of the anatomy of the hamstring

// The mechanism of injury

– Trauma

– Active overstretch

– Passive overstretch

// Location of the injury

// Is it acute or recurrent

// Grade of injury

// The healing process

// Some exercises for recovery

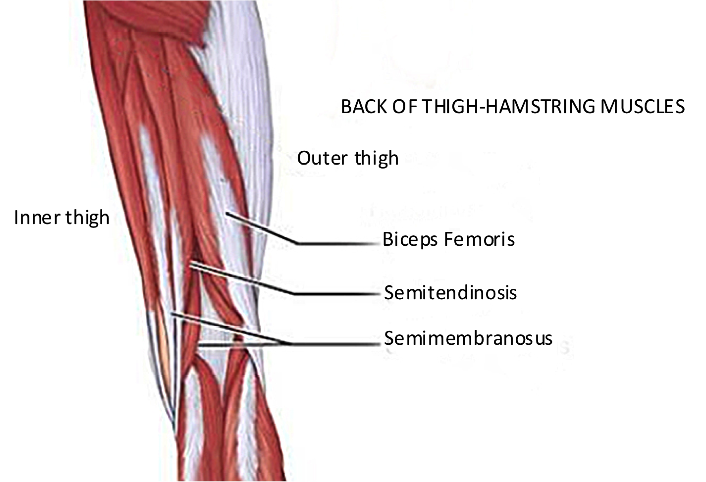

An anatomy review of hamstrings

The ‘hamstrings’ are actually a group of three muscles at the back of the thigh that go all the way from the sit bone (ischial tuberosity) of the pelvis to the shin bone (tibia). Because of their location, the hamstrings are involved with both hip and knee motion, often both at the same time. As becomes very obvious once the muscle is injured or strained (and it hurts to use), the hamstring muscles are involved with many movements of the leg.

Types of hamstring strain and impact on recovery

Despite a significant amount of research into hamstring strain and hamstring injuries and a far greater understanding than a decade ago, it still cannot be said that we yet have the complete picture. In particular, the medical and sports world are working to comprehend prevention of this debilitating condition which is prone to recurrence. An important part of better understanding the injury is sorting or classifying the various different types of hamstring injury, as they are most definitely not ‘all the same’. It’s important to note however, that there are a number of conditions (other than hamstrings injury) that can give back of thigh pain, so it is very important that your physiotherapist clear these other options – especially when there was not an obvious ‘mechanism’ of injury.

Mechanism of hamstring strain (How did the muscle get injured?)

A hamstring injury can occur because of:

// Direct trauma

// Indirect trauma through

– Active overstretch

– Passive overstretch

Trauma

Muscle injury may be direct, like contact trauma, e.g. a bicycle injury incurred by my husband when he fractured his pelvis, plus there was an avulsion fracture of the ischial tuberosity. Direct trauma can also happen as a result of surgeries, e.g. when an ACL is reconstructed and a part of a hamstring tendon is removed to recreate the ligament.

Active overstretch

Active overstretch is also known as a ‘deceleration’ injury, because the hamstring is actively slowing the movement of the leg. This occurs when the hamstring muscle is working whilst it lengthens (eccentric muscle action), but is overcome by the stretching force applied to it and forcibly lengthened. This type of injury (about 3/4 of hamstring strains), generally involves the Biceps Femoris during high speed running, and it is believed to occur during terminal swing phase of the gait cycle as the hamstrings decelerate the leg in preparation for foot contact (2) (note that the hamstrings are not at the limit of range). It is usually accompanied by the sudden onset of pain and an inability to continue the activity. A prime example of this is when James Horwill (captain of Queensland Reds Rugby Union team) injured his hamstring in 2012 (see the video). I warn you it is excruciating to watch! I remember being at this game and felt a little sickened for the poor man.

Passive overstretch

Passive overstretch (about 1/4 of hamstring strains) occurs when a stretch force is applied to the hamstring muscle; this would be what most people would recognise as ‘stretching’, with injury occurring at the limit of range. This sort of injury is commonly seen amongst footballers kicking, or dancers, and generally involves the free tendon of Semimembranosus and amongst dancers was also noted to involve Quadratus Femoris (3). Even if the force is applied slowly (as in a dancer stretching), there may be a pop associated with the injury, though symptoms may not develop for some hours, or only slowly over time, and may not be more than mild discomfort and dysfunction.

The location of hamstring strain

Generally when it comes to hamstring injuries, the closer the maximally tender point is to the buttock, the more likely the injury is to involve tendon tissue and the slower the rehabilitation2.

Whilst the active overstretch or running injury tends to be at the musculo-tendinous junction of the quite lengthy intramuscular Biceps Femoris tendon and adjacent muscle (2), the passive overstretch injury, particularly if pain is felt close to the ischial tuberosity is more inclined to target the tendon, (near but not at the insertion on the bone). Tendons are slow to repair and this latter group of injuries can have a much longer recovery program; at least 6 weeks and often 30-76 weeks (3).

Is the hamstring injury acute or recurrent?

Unfortunately there is a high incidence of recurrence of hamstring injuries; in Australian football 34% of the players reinjured their hamstring muscles within a year of returning to play after their initial hamstring strain injuries (4). Additionally it’s been found that a repeat hamstring injury is usually more severe than the original injury and results in significantly more lost time in comparison to the initial injury (5). Furthermore, there is some suggestion of an impaired healing process in chronic muscle injury that results in excessive inflammation (5).

Grade of hamstring strain

Classically we have sorted muscle injuries into:

Grade 1 When there are some small micro tears in the muscle fibres.

Grade 2 When the muscle fibres have partially torn.

Grade 3 When there is complete disruption to the musculo-tendinous unit.

Nearly all hamstring injuries (about 99%) are Grade 1 or 2, but this grading system is a bit vague and didn’t assist with developing best treatment strategies. So, a few years ago an international consensus (including Australia) agreed on the following (6):

Functional muscle disorders- disorders without macroscopic evidence of fibre tear

Type 1 Overexertion-related

Type 2 Neuromuscular muscle disorders

Structural muscle injuries – macroscopic evidence of fibre tear

Type 3 Partial tears

Type 4 (Sub)total tears/tendinous avulsions

Other factors that may impact on recovery

Pain at onset: the more severe the pain at time of injury, the longer it may take to recover (7)

Age: older athletes frequently take longer to recover and may have a higher risk of re-injury (8)

The healing process

Three phases have been identified in the healing process, and whilst it can be useful to understand these, it must be remembered that healing alone does not dictate recovery and readiness to return to activity. It should also be noted that there isn’t a method for speeding up the healing phases, and appropriate exercise at each stage of management recognises and respects the underlying pathology.

Stage one: Destruction phase, at the time of injury the myofibers and ultra small blood vessels are torn. The formation of a haematoma and ensuing necrosis of the myofibers induces an inflammatory cell reaction that continues for the first few days following injury.

Stage two: Repair phase, begins within a few days of injury and peaks around 2 weeks post injury. It allows regeneration of the myofibers, and simultaneous production of a type of collagen that can be considered pre-scar tissue, as well as capillary ingrowth into the injured area.

Stage three: Remodelling phase, is associated with the production of scar tissue and begins 2-3 weeks following injury. Regenerated myofibers mature, the scar tissue is re-organised and contracts, and the functional capacity of the muscle recovers. The ends of the new myofibers are not re-united but join onto the scar tissue, like they join onto tendon.

There is emerging evidence that NSAID’s (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, like Nurofen) shouldn’t be taken in the first 2 days following injury as they can interfere with the early healing phase. Additionally, continued use (more than 7 days) could delay muscle regeneration (9).

Hamstring strain – treatment and exercises

Phase 1

Treatment is geared towards protecting the hamstring strain from any further injury, and reducing pain using a regime of PRICE:

// Protection (can include modification of walking eg crutches)

// Relative rest, (appropriate gentle movement of the area is good, but range is limited to ensure movement is painfree )

// Ice

// Compression (not too tight)

// Elevation

It’s very important to get pain under control as there is some evidence to suggest that pain inhibition is a significant factor in ongoing eccentric strength deficits in lengthened position (10). Additionally, if the injury is judged to be more tendon than muscle, the principles of staging as recommended by Purdham and Cook (17) come into play, and both tensile and compression loads (18) need to be well managed. This can mean that both stretching and sitting need to be avoided in the early days.

Phase 2

This treatment phase may start as early as day 3, but might continue with many elements of Phase 1 (it depends on how severe the injury is). Biomechanical / neurodynamic issues may need addressing and some neuromuscular/ proprioeptive training is included providing it is painfree: ie. lumbo-pelvic control/ stability initially low load and low speed and not in the same plane in which the hamstring injury occurred, progressing in speed, intensity, and into the sagittal plane. Additionally, at day 5, if appropriate, the program will also incorporate some gentle painfree eccentrically focussed exercises as shown in a study by Askling et al (11), (see below), to accelerate recovery (this is not quicker healing, but functioning at a higher level with less pain) and proceeding to earlier return to activity than traditional rehabilitation programs (typically 4 weeks vs 7). Some gentle jogging will also be included in this phase of treatment (if applicable), but it’s important to note that whilst the client might be feeling quite good at this stage, healing is still in the early days and the injury is vulnerable to further injury.

Particular care with the exercises is required, if at the beginning of Phase 2 walking isn’t painfree and other test criteria are not met, and introduction of some of the active components of the program may need to be delayed or modified. The Physiotherapist will guide through these decisions. Additionally, for the ‘passive stretch’ injury, where the main deficit is often flexibility, the recommendation is to include active voluntary exercises to increase range of motion (hip flexion with different extension angles at the knee) instead of passive stretching because passive stretching seems to provoke more pain and can overstress the healing tissue (15). Alternatively, for this type of injury, it’s recommended to consider foam roller or trigger point work rather than stretching as the latter places both a tensile and compression load on the tendon (18).

The Extender: the player should hold and stabilise the thigh of the injured leg with the hip flexed approximately 90° and then perform slow knee extensions to a point just before pain is felt. Twice every day, three sets with 12 repetitions. Goal is to increase flexibility.

A movement studio equivalent, Foot in Strap, or if too early in recovery stage a cuff strap around the thigh and have the person bend and straighten their leg.

The Diver: the exercise should be performed as a simulated dive, that is, as a hip flexion (from an upright trunk position) of the injured, standing leg and simultaneous stretching of the arms forward and attempting maximal hip extension of the lifted leg while keeping the pelvis horizontal; angles at the knee should be maintained at 10–20° in the standing leg and at 90° in the lifted leg. Owing to its complexity, this exercise should be performed very slowly in the beginning. Once every other day, three sets with six repetitions. Combined ex for strength & trunk/pelvis stability.

The Glider: the exercise is started from a position with upright trunk, one hand holding on to a support and legs slightly split. All the body weight should be on the heel of the injured (here left) leg with approximately 10–20° flexion in the knee. The motion is started by gliding backward on the other leg (note low friction sock) and stopped before pain is reached. The movement back to the starting position should be performed by the help of both arms, not using the injured leg. Progression is achieved by increasing the gliding distance and performing the exercise faster. Once every third day, three sets with four repetitions. Goal is specific strength training.

On the CoreAlign. Reformer progression could be where the person is standing on the platform with their back leg on the carriage and pressing backwards.

Phase 3

Phase 3 for the ‘active stretch’ injury is not an automatic progression based on healing, but a clinical progression based on being painfree jogging forward and backward at moderate pace and having full strength on manual muscle testing. The exercise program is gradually progressed to high level agility and sport specific drills, high level eccentric work, possibly including Nordic curls as there is evidence that Nordic Hamstring exercises (eccentric training) reduce the incidence of both new and recurrent hamstring injuries (12).

A recent study by Bourne et al (16) evaluated a variety of hamstring exercises and found that in comparison to the Nordic curl, the 45° hip extension exercise preferentially targeted the lateral hamstring (biceps femoris- site of most hamstring injuries) over the medial hamstrings. This was especially true for eccentric strength. Although it is too early to tell if this will be a game changer in hamstring injury management and prevention it is worthy of inclusion in the overall plan, as it is acknowledged that eccentric knee flexor weakness is a risk factor for hamstring injury (8).

The rehab program also progresses to include high speed eccentric conditioning (sprinting), as well as emphasizing varying trunk movements during running (eg, upright posture, forward flexed, forward flexed and rotated). The latter was shown to reduce hamstring injury occurrence by 70% on average over a 2 year period, so should be included as part of a comprehensive rehabilitation where appropriate (14). For the ‘passive stretch’ injury, research tells us that return to activity will be slow, with a high risk of recurrence (3) and understanding this is perhaps key to optimal recovery for those with this type of hamstring injury. Additionally, the principles of tendon rehabilitation come to the fore with this type of injury, and continued graduated increase in both tensile and compressive forces is a critical part of optimal management. In particular, running uphill places high compression and tensile forces on the tendon, and needs to be introduced very carefully, monitoring for latent response to load (24-48 hour delay) and managing ‘recovery’ appropriately after exercise.

Some exercises that may be appropriate in the rehabilitation of hamstring injuries are the following. These exercises can also be considered very relevant as part of the hamstring preparation work for prevention of injuries.

Phase 4

Phase 4 is return to sport. As there is a high recurrence rate of hamstring injuries, the hamstring confidence test proposed by Askling et al shows promise for functionally evaluating a return to sport with a much reduced risk of re-injury (13).

This article was prepared as part of our research and preparation for several of our workshops including:

// Body Organics – Working with Runners course that is to be delivered in Australia and Spain in 2017 ( and any other country interested) delivered by Mauricio Bara Physiotherapist and Exercise Physiologist and Manual Alcazar Roja. The course is conducted in either English or Spanish.

// Body Organics – Pilates Stands Up the application of the Core Align apparatus into a pilates studio setting

References

1. http://www.aflcommunityclub.com.au/fileadmin/user_upload/Play_AFL/Multicultural/2013_AFL_Injury_Report.pdf (AFL Injury Report 2013, Orchard J, Seward H, Orchard, J)

2. Askling CM, Tengvar M, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Acute first-time hamstring strains during high speed running: a longitudinal study using clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Am J Sports Med 2007; 35:197-206.

3. Carl M. Askling, Magnus Tengvar, Tönu Saartok, Alf Thorstensson Acute First-Time Hamstring Strains During Slow-Speed Stretching Clinical, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, and Recovery Characteristics., Am J Sports Med October 2007vol. 35 no. 10 1716-1724

4. J. Orchard, H. Seward. Epidemiology of injuries in the Australian football league, seasons 1997–2000 Br J Sports Med, 36 (2002), pp. 39–44.

5. J. Orchard, T.M. Best . The management of muscle strain injuries: an early return versus the risk of recurrence Clin J Sport Med, 12 (2002), pp. 3–5)

6. Terminology and classification of muscle injuries in sport: The Munich consensus statement. Hans-Wilhelm Mueller-Wohlfahrt, Lutz Haensel, Kai Mithoefer, Jan Ekstrand, Bryan English, Steven McNally, John Orchard, C Niek van Dijk, Gino M Kerkhoffs, Patrick Schamasch, Dieter Blottner, Leif Swaerd, Edwin Goedhart, Peter Ueblacker, Br J Sports Med 2013;47:342-350 doi:10.1136/bjsports-2012-091448, 18 October 2012

7. Verrall GM, Slavotinek JP, Barnes PG, Fon GT. Diagnostic and prognostic value of clinical findings in 83 athletes with posterior thigh injury. Comparison of clinical findings with magnetic resonance imaging documentation of hamstring muscle strain. Am J Sports Med 2003; 31:969-973.

8. Verrall GM, Slavotinek JP, Barnes PG, Fon GT, Spriggins AJ. Clinical risk factors for hamstring muscle strain injury: a prospective study with correlation of injury by magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Sports Med.2001;35:435–439. discussion 440

9. F. T. G. Rahusen, P. S. Weinhold, and L. C. Almekinders, “Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen in the treatment of an acute muscle injury,” American Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 32, no. 8, pp. 1856–1859, 2004.

10. Fyfe JJ, Opar DA, Williams MD, et al The role of neuromuscular inhibition in hamstring strain injury recurrence.. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2013;23:523–30. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2012.12.006

11. Carl M Askling, Magnus Tengvar, Alf Thorstensson. Acute hamstring injuries in Swedish elite football: a prospective randomised controlled clinical trial comparing two rehabilitation protocols.. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:953-959 doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092165

12. Petersen J1, Thorborg K, Nielsen MB, Budtz-Jørgensen E, Hölmich P. Preventive effect of eccentric training on acute hamstring injuries in men’s soccer: a cluster-randomized controlled trial.. Am J Sports Med. 2011 Nov;39(11):2296-303. doi: 10.1177/0363546511419277. Epub 2011 Aug 8.)

13. Askling, c. m., Nilsson, j. & Thorstensson, A. 2010. A new hamstring test to complement the common clinical examination before return to sport after injury. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 18, 1798-803.

14. Verrall GM, Slavotinek JP, Barnes PG. The effect of sports specific training on reducing the incidence of hamstring injuries in professional Australian Rules football players. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:363–368

15. Sherry MA, Best TM. A comparison of 2 rehabilitation programs in the treatment of acute hamstring strains. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:116-125.

16. Matthew N Bourne, Morgan D Williams, David A Opar, Aiman Al Najjar, Graham K Kerr, Anthony J Shield. Impact of exercise selection on hamstring muscle activation http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/early/2016/05/13/bjsports-2015-095739

17. Cook JL, Purdam CR Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of load-induced tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2009 Jun;43(6):409-16. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.051193. Epub 2008 Sep 23.

18. Cook JL, Purdam C Is compressive load a factor in the development of tendinopathy? Br J Sports Med. 2012 Mar;46(3):163-8. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090414. Epub 2011 Nov 22.

0

0