Shouldering On: Shoulder exercises and considerations for Pilates studios

Sun,Sep 30, 2018 at 04:40PM by Carla Mullins

Shoulder pathology and shoulder exercises for Pilates and movement studios

The shoulder complex is tricky because its inherent range of motion can compromise joint stability, so often we have to “shoulder on” despite the pain. It is of little surprise that shoulder pain is the third most common cause of consultations for musculoskeletal pain in primary health care (Brox, et al, 2010). Shoulder pain can arise from many structures around the shoulder, neck and chest, with symptoms radiating over the joint, neck and down the arm. This article is part of a series in which we will be looking at some common shoulder problems seen in a movement studio, many of which require a basic understanding of upper limb organisation. Shoulder exercises are outlined supported by video instructions.

In this article we look at:

// Common contributors to shoulder pain;

// Anatomical patterning that happens in the shoulder complex;

// Ways to cue and teach some common exercises in order to achieve good movement pattern and to avoid shoulder problems or to minimise pain.

In subsequent articles we shall look at:

// Frozen shoulder (also known as adhesive capsulitis);

// Clavicular injuries;

// Rotator cuff injuries.

This article will highlight some patterns and possible injuries that can be evident in the non-traumatic population of clients with shoulder pain. Examples of poor movement patterns will be outlined to remind us of which shoulder exercises we should or should not be using or modifying in a movement setting. It can be read in conjunction with our previous article on arm movement patterning.

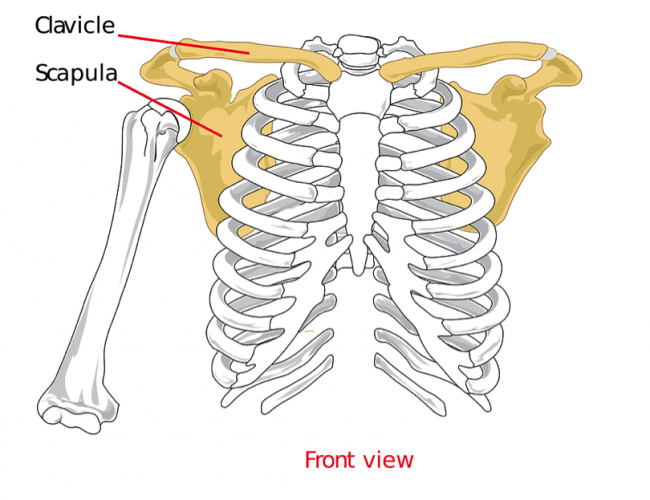

A quick review of the shoulder anatomy

Let’s now review the anatomy of the shoulder complex to give a deeper understanding of pain or injuries that can occur. The shoulder complex consists of the following bones:

// Clavicle (collar bone);

// Scapula (shoulder blade);

// Sternum;

// Ribcage;

// Humerus.

These bones make up four joints:

// Sternoclavicular;

// Acromioclavicular;

// Glenohumeral;

// Scapulothoracic.

Each component is required to achieve functional and pain free movement. Most injuries and syndromes occur at the glenohumeral joint (i.e. where the arm sits in the socket of the shoulder blade), with dysfunctional movement patterns in the scapulo-thoracic joint (i.e. how the scapular sits and moves on the rib cage), both contributing to and resulting from what is happening at the glenohumeral joint. This interrelationship can be attributed to the large range of motion within both joints, their reliance on muscles for stability and their dependence on each other for adequate movement.

The glenohumeral joint is a ball and socket joint and therefore one of the most mobile joints in the human body. This is due to the anatomy of the shoulder joint itself (think of a golf ball sitting on a tee) and the fact its stability is provided by the same muscles that have a role in dysfunctional movement patterns of the glenohumeral and scapulothoracic joint. These muscles include:

// Rotator cuff and other related muscles, specifically the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, teres major, subscapularis, and biceps brachii;

// Scapula stabilisers – serratus anterior, serratus posterior superior, middle and lower trapezius, rhomboids, levator scapulae;

// Prime movers – deltoid, latissimus dorsi, pectoralis muscles, upper trapezius.

Injuries or postural dysfunction (tightness) in these muscles or the capsular ligaments are common and often lead to much bigger problems in the shoulder and neck.

Scapulothoracic joint is key to shoulder pain

The scapulothoracic joint (also known as scapulocostal joint) is key to shoulder pain as it controls the position of the glenoid socket (in which the humeral head rests) and the rotator cuff muscles as they attach to the scapular and the humeral head. If the glenoid socket is poorly positioned then tendons, muscles and capsule can pinch and become irritated. From this point, with continual load (movement), other tendons, ligaments, nerves and structures can become irritated. You may see injuries such as bicep or rotator cuff tendon tears develop due to impingement (pinching) secondary to dysfunctional scapulothoracic patterning. To correctly position the scapula, significant muscle strength and coordination is required between the clavicle, scapula and the humerus. If there is tightness, under activity or poor timing in recruitment of scapula stabilisers, it will result in poor placement of the glenoid socket because of the incorrect scapula placement.

What can go wrong with shoulders?

Probably the most common problem is seen in shoulder flexion (reaching above the head as the arm moves up at the front of the body) and abduction (reaching above the head as the arm moves up from the side of the body). In a day-to-day activity that could include lifting a child above their head; in a studio setting this could include lifting a weight or working with the Ped-O-Pull or on some Pilates reformer exercises.

Good quality shoulder flexion and abduction requires the joints to be functional. This means that the:

// Glenohumeral joint needs the humeral head to slide along the surface of the socket and be able to move into external rotation;

// Scapula needs to be both stable and dynamic to achieve smooth controlled movement as it moves along the chest wall. This is referred to as scapulohumeral rhythm;

// Sternoclavicular and acromioclavicular joints need to be able elevate and rotate posteriorly.

Try this by taking your arm above your head with the palm facing in front of the body. This external rotation will facilitate more range into both abduction and flexion than if you perform the same movements with palms facing behind the body. Then place one hand on your collarbone with the tips of your fingers curled around the surface of the collarbone with your palm facing the front of your body and lift your arm out to the side. As you do so, you will feel your collarbone elevate and posterioraly rotate. If your shoulder as a whole lacks these ranges of movement then shoulder pain and/or dysfunction quickly develops.

Some ideas when teaching Pilates exercises for shoulders

There are four basic concepts I like to consider when working with shoulders, pathological or not. These concepts are:

// Achieve appropriate humeral head placement within the glenohumeral socket (i.e. external rotation);

// Ensure the correct scapulohumeral rhythm in exercises such as waving on the spine corrector (ie upward rotation of the shoulder blade while in retracted position);

// Maintain correct subacromial space (i.e. able to move while maintaining the above external rotation and retraction);

// Look at the posture of the trunk and how that may contribute to poor movement patterns (i.e. the lack of thoracic extension in shoulder flexion and abduction).

Concept One: Achieve appropriate humeral head placement within the glenohumeral socket

Concept Two: Ensure the correct scapulohumeral rhythm in exercises such as waving on the spine corrector (as found in the Barrel and Arc manual)

Concept Three: Maintain correct subacromial space

Concept Four: Look at the posture of the trunk and how that may contribute to poor patterning or supporting strength

Pathological shoulders

Pathological shoulders (I love saying that term, it makes me have flashbacks to the 80’s shoulder pads in shows like Dynasty) often present with tight:

// Pectorals

// Latissimi

// Anterior deltoids

This is often caused due to long periods spent in a hunched or rounded shoulder position, such as sitting at a desk. Think about Concept Four we mentioned above. In contrast, many throwing or overhead athletes can overstretch these muscles, leading to a complex laxity problem at the joint.

Poor cueing for shoulder exercises

Furthermore, poor cueing of movement for shoulder exercises, such as restricting external rotation of the humeral head or over activity of the upper trapezius, is sometimes exacerbated by coaches and teachers who encourage the lift of the arms in unnatural positions (see article joint patterning of the arms). An example of what is often taught in these sort of situations is Salute / Tiara or Bicep Curl. In these exercises poor patterning can impinge the shoulder. In the video below we seek to show examples of how things can be affected or how impingement can occur if correct movement patterns are not considered. I have uploaded several videos on the arms series and tips for teaching them properly to our YouTube channel Body Organics Education.

Shoulder injuries within glenohumeral joint

Injuries within the glenohumeral joint can best be described as an imbalance in tissue flexibility and strength resulting in other tissues to become overloaded in an attempt to compensate. These chronic injuries are directly associated with poor scapulothoracic control and stabilisation. With decreasing stability within the glenohumeral joint due to minor injuries, repetitive overstretching or muscle weakness, the dynamic stabilisers of both the glenohumeral and scapulothoracic joints become fatigued and movement dysfunctions occur. The compounding factors of joint laxity, poor dynamic stabilisers and a dysfunctional movement pattern results in multiple pathologies occurring at the shoulder complex. For shoulder exercises in a movement class we address the patterns through the focus on the detail and precision of movement to avoid injuries or to address the causes for those injuries.

In conclusion, what is important when we move the arm in shoulder exercises?

When we work with clients to move their arm in shoulder exercises, whether it is because of an injury or to avoid an injury, it is important to focus on some key principles that we explore as part of the Anatomy Dimensions courses:

// Subacromial space;

// Scapula glide and slide on the rib cage and around the humeral head;

// Humeral head spiral in the glenohumeral socket (external and internal rotation e.g. correct joint patterning in Pilates Hundreds);

// Sternal glide and slide;

// Capsule stability, that is we are not losing the humeral connection (congruency) to the socket by pressing into the stabilising capsule around it;

// Thoracic mobility and facet joint mobility, which is covered in this article on Thoracic and Diaphragmatic Mobility;

// Clavicular and neck placement, particularly so that the nerves are not compressed;

// Pelvic stability, particularly through the anterior and posterior oblique muscular slings, as depicted in the rotator cuff exercise video earlier in this article.

Below is a small video on how to use Makarlu and other props in a class and as part of a person’s home program

Shop MakarluThis article was written by Carla Mullins and Doug Wilson (Physiotherapist).

Correct joint patterning and movement principles as well as dealing with specific injury types are detailed more thoroughly in the Diploma for Pilates Movement Therapy NAT10567 but also in our Anatomy Dimensions courses for the Upper Limbs. For the first part of 2020 we will be offering courses throughout

// Australia

// USA

// Central and South America

If you are wanting ore information about our courses or wanting to host us please contact us info@bodyorganicseducation.com

0

0